Debt-to-Equity Ratio: What It Means to You

A debt-to-equity-ratio that’s high compared to others in a company’s given industry may indicate that that company is overleveraged and in a precarious position. Other companies that might have higher ratios include those that face little competition and have strong market positions, and regulated companies, like utilities, that investors consider relatively low risk. A company’s…

A debt-to-equity-ratio that’s high compared to others in a company’s given industry may indicate that that company is overleveraged and in a precarious position. Other companies that might have higher ratios include those that face little competition and have strong market positions, and regulated companies, like utilities, that investors consider relatively low risk. A company’s ability to cover its long-term obligations is more uncertain, and is subject to a variety of factors including interest rates (more on that below).

Online Investments

- If the D/E ratio gets too high, managers may issue more equity or buy back some of the outstanding debt to reduce the ratio.

- The reason for this is there are still loans that need to be paid while also not having enough to meet its obligations.

- Investors who want to take a more hands-on approach to investing, choosing individual stocks, may take a look at the debt-to-equity ratio to help determine whether a company is a risky bet.

- The value of Bonds fluctuate and any investments sold prior to maturity may result in gain or loss of principal.

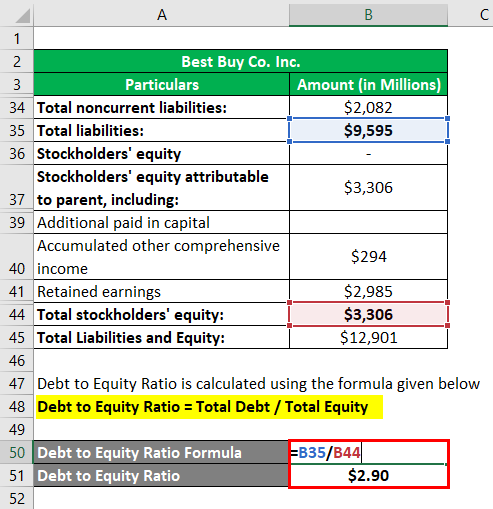

While a useful metric, there are a few limitations of the debt-to-equity ratio. It’s clear that Restoration Hardware relies on debt to fund its operations to a much greater extent than Ethan Allen, though this is not necessarily a bad thing. This figure means that for every dollar in equity, Restoration Hardware has $3.73 in debt. The following D/E ratio calculation is for Restoration Hardware (RH) and is based on its 10-K filing for the financial year ending on January 29, 2022. As noted above, the numbers you’ll need are located on a company’s balance sheet. Depending on the industry they were in and the D/E ratio of competitors, this may or may not be a significant difference, but it’s an important perspective to keep in mind.

Can the D/E ratio vary by industry?

Banks carry higher amounts of debt because they own substantial fixed assets in the form of branch networks. Higher D/E ratios can also tend to predominate in other capital-intensive sectors heavily reliant on debt financing, such as airlines and industrials. As a highly regulated industry making large investments typically at a stable rate of return and generating a steady income stream, utilities borrow heavily and relatively cheaply. High leverage ratios in slow-growth industries with stable income represent an efficient use of capital. Companies in the consumer staples sector tend to have high D/E ratios for similar reasons.

What Does the Debt-to-Equity Ratio Tell You?

The Debt to Equity ratio is a financial metric that compares a company’s total debt to its shareholder equity. Including preferred stock as debt can inflate the D/E ratio, making a company appear riskier, whereas counting it as equity would lower the ratio, potentially misrepresenting the company’s financial leverage. This issue is particularly significant in sectors that rely heavily on preferred stock financing, such as real estate investment trusts (REITs). The debt to equity ratio is calculated by dividing total liabilities by total equity. The debt to equity ratio is considered a balance sheet ratio because all of the elements are reported on the balance sheet.

Q. Can I use the debt to equity ratio for personal finance analysis?

Other industries that tend to have large capital project investments also tend to be characterized by higher D/E ratios. However, a low D/E ratio is not necessarily a positive sign, as the company could be relying too much on equity financing, which is costlier than debt. A challenge in using the D/E ratio is the inconsistency in how analysts define debt. Let’s examine a hypothetical company’s balance sheet to illustrate this calculation. Yes, the ratio doesn’t consider the quality of debt or equity, such as interest rates or equity dilution terms. The cash ratio compares the cash and other liquid assets of a company to its current liability.

In fact, debt can enable the company to grow and generate additional income. But if a company has grown increasingly reliant on debt or inordinately so for its industry, potential investors will want to investigate further. Gearing ratios focus more heavily on the concept of leverage than other ratios used in accounting or investment analysis. The underlying principle generally assumes that some leverage is good, but that too much places an organization at risk.

Including preferred stock in the equity portion of the D/E ratio will increase the denominator and lower the ratio. This is a particularly thorny issue in analyzing industries notably reliant on preferred stock financing, such as real estate investment trusts (REITs). Short-term debt also increases a company’s leverage, of course, but because these liabilities must be paid in a year or less, they aren’t as risky.

Taking a broader view of a company and understanding the industry its in and how it operates can help to correctly interpret its D/E ratio. For example, utility companies might be required to use leverage to purchase costly assets to maintain business operations. But utility companies have steady inflows of cash, and for that reason having a higher D/E may not spell higher risk. If preferred stock appears on the debt side of the equation, a company’s debt-to-equity ratio may look riskier.

The simple formula for calculating debt to equity ratio is to divide a company’s total liabilities by its total equity. There are several metrics that are used to gauge the financial health of a company, how the company finances its business operations and assets, as well as its level of exposure to risk. Another popular iteration of the ratio is the long-term-debt-to-equity ratio which uses only long-term debt in the numerator instead of total debt or total liabilities. This second classification of short-term debt is carved out of long-term debt and is reclassified as a current liability called current portion of long-term debt (or a similar name). The remaining long-term debt is used in the numerator of the long-term-debt-to-equity ratio. It suggests that a company relies heavily on borrowing to fund its operations, often due to insufficient internal finances.

The results of their IPO will determine their debt-to-equity ratio, as investors put a value on the company’s equity. For example, if a company takes on a lot of debt and then grows very quickly, its earnings could rise quickly as well. If earnings outstrip the cost of the debt, which includes interest payments, a company’s shareholders can benefit and stock prices may go up. For example, if a company, such as a manufacturer, requires a lot of capital to operate, it may need to take on a lot of debt to finance its operations. A steadily rising D/E ratio may make it harder for a company to obtain financing in the future. The growing reliance on debt could eventually lead to difficulties in servicing the company’s current loan obligations.

Strategic management of this ratio is crucial for long-term financial health. If a company’s debt to equity ratio is 1.5, this means that for every $1 of equity, the company has $1.50 of debt. For someone comparing companies in these two industries, it would be impossible to tell which company makes uniform capitalization rules better investment sense by simply looking at both of their debt to equity ratios. If you are considering investing in two companies from different industries, the debt to equity ratio does not provide an effective way to compare the two companies and determine which is the better investment.